In the aid world, a series of reflections on the unintended negative impact of international aid in conflict-affected contexts, and a long-term research project by the Collaborative for Development Action in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide events, led to the development of the “Do-no-Harm approach.” This approach has greatly increased INGO’s awareness of and reflection on the importance of working with everyone on the same level and focusing on technical support. Many organizations, including Helvetas, engage in eye-level dialogue and exchange on the analysis and implementation level.

Yet, when working in conflict-affected contexts, be it with a focus on conflict-sensitive development, humanitarian aid, or transforming conflicts and building peace, we are immediately confronted with positionalities: how people position themselves in terms of the conflict(s) at stake, the roles they assume we have, the individual positions of our staff and partners involved in the project toward the different conflicts, to name a few. Mostly, those positionalities are neither made transparent nor discussed; except for those of the main actors in the conflict, during conflict analysis.

Here are some challenging situations we found ourselves in over the last couple of years:

In West Africa, we started a workshop and were soon interrupted by a participant, asking us why and with what right we came to “teach” them about how to deal with their conflicts when we – he meant Europeans and referred to a particular nationality – were the ones responsible for the mess they now must cope with.

In Southeast Asia, in a highly contested conflict context, we were asked to challenge some of our partner’s collaborators’ discriminating viewpoints without “teaching” them what was right or wrong. Our project would have been at risk if we had not managed to change the group’s attitudes and behavior towards an ethnic group in a subtle, effective and sustainable manner.

When people with completely different backgrounds and life experiences collaborate, there is often some tension that – if not taken care of with diligence – can put fruitful cooperation at risk.

Positionalities, perceptions, prejudices

Our life experience shapes our positions: where and by whom we were raised, the groups we feel we belong to, the stories we were told, and the experiences we went through. All of this influences how we think about and interact with others as we grow up. The more our worlds overlap, the more we feel we belong. The less overlap we have with others, the less we tend to trust them. Humans’ negative perception of the other intensifies in conflict-affected contexts[1]: Our fear increases, we consider others as a threat, we polarize more, and our positions harden.

Positionalities in practice: sensibly and sensitively dealing with differing perceptions

Helvetas has experienced positionality challenges when promoting women’s rights in political participation, access to justice, or land property. We are also sometimes challenged to question our values regarding political systems: to what extent is our assumption that democratic systems work best in any context adequate? Often, what we try to achieve goes against cultural norms. It is therefore delicate to navigate systemic changes around good governance. Working on such change processes in a sensitive manner takes time and must include a wide range of actors.

In contexts with severe conflicts, it is particularly difficult for our local staff to work impartially, as they tend to empathize with some conflict parties more than with others. Yet, expats can also be challenged with positionalities: we all tend to judge, generalize, and compartmentalize people. It is then our task to question our prejudice and deal with it constructively, to remain professional, and conflict-sensitive.

How has this insight informed our work since then, and how did we deal with the situations described earlier?

In the past, our Helvetas “Conflict-Sensitive Programme Management” (CSPM) methodology had a rather technocratic focus. We taught our staff and partners to include our organization and projects in their conflict analysis. However, a few years back, we realized that knowing that we automatically perceive others and are perceived by others in certain ways and being aware of the consequences this entails is a prerequisite for working conflict-sensitively. Thus, we introduced another level of analysis in our approach: the individual level. It entails:

- analyzing how our and others’ attitudes and behavior towards others have been shaped by our and others’ socialization.

- reflecting on how our attitudes and behavior shape our relations with others.

- reflecting on how to mitigate potential tension, e.g., by engaging with the actors that might have a negative impression of us and build trust or by being cautious with proximities that might be perceived as suspicious by other actors.

- including all these reflections in our conflict-sensitivity analysis and strategy.

In the situation described above in West Africa, our strategy was to listen to the participant and show empathy. We explained that all opinions were welcome and it was precisely due to such issues that we created a space to discuss ways to deal with tensions more constructively and thus contribute to the population’s well-being. At the end of the workshop, the same participant thanked us for offering a friendly atmosphere, where bridges and trust were built, which seemed impossible to him before.

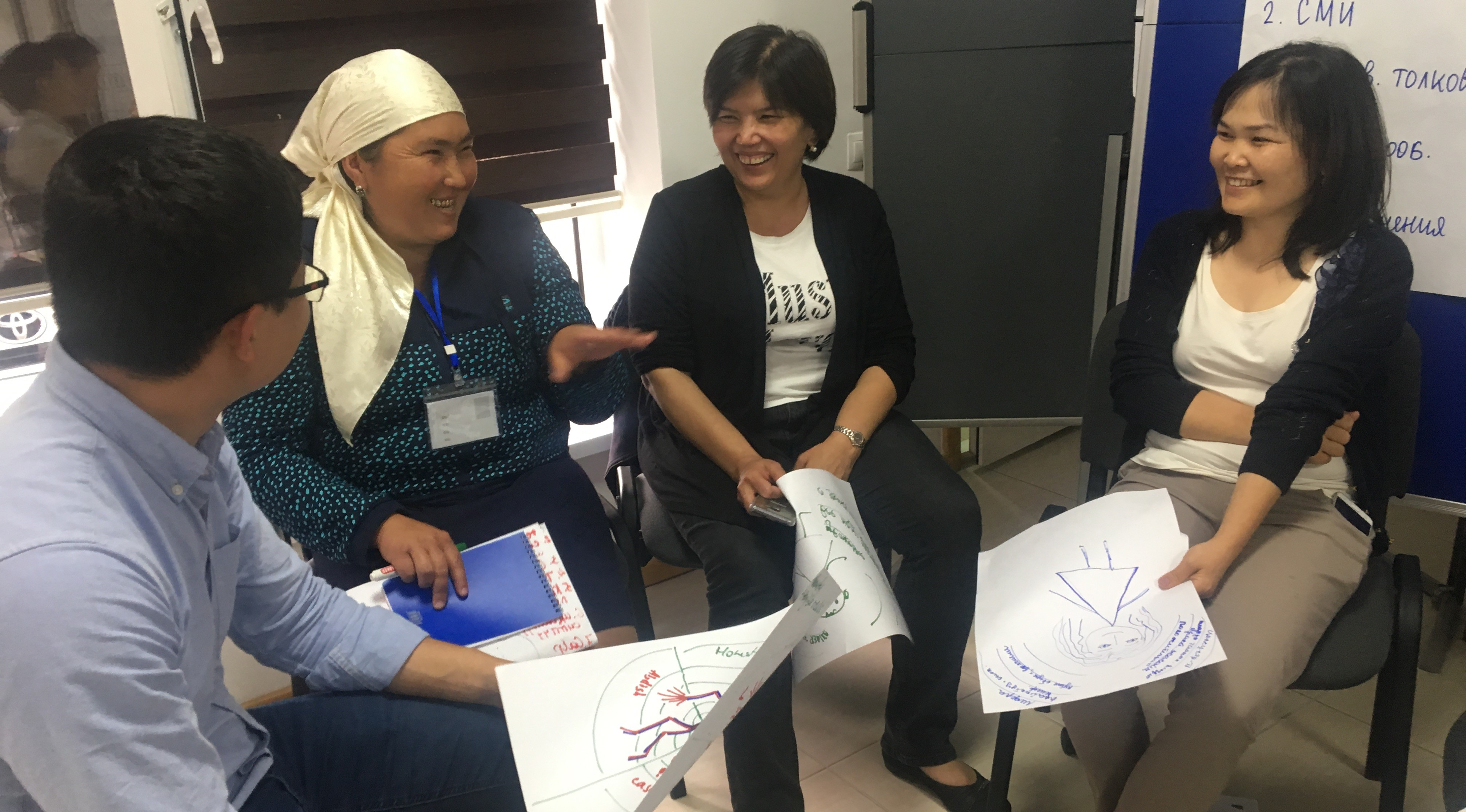

In Southeast Asia, we invited our partner’s collaborators to a workshop to create common ground and a fruitful basis for our collaboration. We carried out exercises that helped them to stand in the shoes of those they had negative prejudice towards. These simulations greatly moved the collaborators, which allowed for a shift in their perception. A thorough reflection of the exercises helped to minimize their suspicion against other groups and increased their understanding of others. The group developed a more pluralistic and equitable attitude, understood the need for social cohesion, and finally agreed that all ethnic and religious groups in the country deserved the same rights and treatment.

Lessons learned & conclusions

We believe that professional peace and development workers with a Western background have significantly enhanced their awareness of positionalities and their sensitivity towards political economies, power relations, and conflicts.

At Helvetas, positionality challenges prevail mostly in contexts marked by neo-colonialism, for example, through European or American military presence, when working with new partners, until we have established a reputation as an equitable partner doing locally relevant and impactful work. Positioning ourselves as “tools” for idea-generation and facilitators of processes for mutual learning often helps to foster trust and create good relations.

Despite this, there is still room for improvement regarding the methods addressing positionalities in our work. Therefore, we are working on:

- developing a curriculum fostering more self-awareness and reflection for our staff and partners focusing on being conflict-sensitive. This training has been piloted in Mozambique and Mali and is now requested in many other countries;

- regular learning & exchange sessions on conflict sensitivity on all levels to internalize conflict sensitivity in our staff’s heads, hearts, and hands – and building up focal points in all countries who can train and facilitate support to our partners, too.

- starting an internal exchange on working in a trauma-informed way.

We still have much to learn and improve to enable collaboration on an equal playing field. Let us jointly explore more ways to do this and share our experiences!

[1] Le Shan, L. (1992). The Psychology of War. Chicago: Noble Press.