This interview was published here on November 29, 2019.

Since November 21, protests have been taking place across Colombia against the government’s neo-liberal policies, against violence, and in favor of peace. News of repressive violence, the death of 18-year-old Dilan Cruz, and the citizens’ response in the form of “cacerolazos” is making headlines internationally. ask! interviewed Camilo González Posso, President of Indepaz (Institute for Peace and Development) and Director of the Centro de Memoria Historica project in Bogotá.

ask: Camilo, can you tell us what’s happening in Colombia at the moment?

Camilo González: We’ve now already reached the seventh day of the National Strike in Colombia. Originally organized for November 21 with marches and strikes in certain public and private companies, the strike has turned into a continuous wave of mobilization with millions of people and a number of different reasons for protesting.

ask: Who is on the strike committee?

C.G.: The committee that called the strike is made up of trade unions, student organizations, indigenous people, smallholder farmers, women, and communities. They represent the majority of organized sectors from over 500 urban centers and municipalities in the country. Although the strike committee was responsible for organizing the strike and starting the ball rolling on November 21, the movement is now gaining a great deal more momentum and new forms of mobilization have arisen that have a different logic to that of traditional marches and strikes with a unified leadership. People are mobilizing in every region and city, with slogans and feelings being unbelievably in sync in this stand against the government’s anti-social policies and defense of life and peace.

ask: What do you make of the repression from the police and military?

C.G.: Over these past seven days, millions of people have peacefully mobilized themselves. They have campaigned against violence, the killing of social leaders, and the use of warfare techniques such as the militarization of certain areas and the authorization of indiscriminate bombardments, including those that claimed the lives of 12 children and which were justified by the government. It is a movement against war and in favor of peace which condemns all types of violence, even that within the context of demonstrations. The riot police responded with excessive violence to this impressive demonstration of self-control on behalf of young people and mobilized society. This has resulted in hundreds of injuries and four deaths so far, including of young Dilan Cruz, who was killed by a police officer in Bogotá using a non-conventional weapon at point-blank range.

The peaceful mobilization is evident in pictures showing demonstrators welcoming police officers that are passive and non-violent as well as in the rejection of infiltrators and saboteurs, which appear to be part of the police force in some cases. In Santander de Quilichao (Cauca), an attack on a police station left two police officers dead and nine injured. The reaction of the population was a total rejection of these local armed groups or drug smugglers that continue to be active in certain areas. We are facing a peace mobilization, which has come about partly as a result of the new sentiment following the signing of the peace agreement, in which guns have given the floor to the voices of the citizen protest.

ask: What’s the situation like now? Have the police and military used less violence given the countless complaints about the exorbitant use of physical force?

C.G.: The national and international rejection of the excessive use of violence has mitigated the brutality of the repression, although critical situations still exist. International human rights organizations, including the office of Ms. Bachelet, have called upon the government to refrain from deploying the military in the repression against social protest and to limit themselves to police methods when controlling public order. Up until now, the military with its warfare has been deployed in the background to ensure safety, looming large on interurban roads with protective infrastructure and the intimidating mobilization of tanks, among other forms of intimidation. The military, however, has not been used in the direct repression on the streets and in the districts. There have been instances of strong militarization such as curfews in several cities (Bogotá, Cali, Popayan, Manizales), especially during the nights of November 21 and 22. This militarization and these curfews, together with permission to shoot anyone found on the streets, was legitimized with a wave of panic that spread in some cities with rumors that “vandals” in “hordes” would soon be invading housing complexes and market spaces. The climate of fear and panic set the stage for military action.

ask: Who do you think is behind these rumors about so-called “vandals”?

C.G.: The rumors about “vandals” having apparently prepared themselves to raid on the day of the National Strike were already circulating in the week before the strike. They have become part of the discussions and questions resulting from pictures of raids in Chile and Bolivia, which were inflated in the media. It is likely that this has alleviated the tasks of certain structures in the security field, which are experts in using fear as a strategy to control the population. In the language of national security, the supreme government authorities and the ruling party spread the message that the strike was an international terrorist conspiracy intended to destabilize the Duque government; they also deemed it the work of the “Saõ Paulo Forum” implemented by troublemakers paid by Maduro. This rumor led to borders being closed, foreigners being deported, and talks of preparing for war making the rounds.

ask: Unbelievable.

C.G.: People responded in extraordinary ways: namely with the sound of “cacerolazos” (banging on empty pots and pans) with parties in living quarters and get-togethers with neighbors during the evenings and nights. Entire families are going onto the streets to make noise with drums and chant slogans against repression and the government.

ask: How do you see the strike in Colombia in relation to the other demonstrations and movements currently in full swing in Latin America?

C.G.: The logic behind what is going on varies from country to country, but we are ultimately on the verge of an international movement that protests against the anti-social and anti-democratic policies of exclusionary globalization. Just like in Ecuador and Chile, the protests in Colombia are against the government’s proposed measures, i.e. against a new wave of neo-liberal policies driven forward by the IMF and OECD. These negatively impact the majority of the population. We are facing a revolution of consciousness of great significance. It is a response to an economic and social model that offers hopelessness and inequality and is defended by authoritarianism.

This revolution of consciousness is a common denominator in our countries. Millions of people are taking a stand against a model that discriminates against young people and women, that supports the rules of multi-national companies, and that privatizes everything right up to the most important public services. On top of this, there are calls for equality, respect for nature, the rejection of corruption, the rejection of the enforcement of neoconservatism, and the rejection of a despotic and authoritarian regime.

ask: Do you know anything about what Duque’s proposed “National Dialogue” (“Conversación Nacional”) involves?

C.G.: Duque, in a state of obvious helplessness, tried to stall his response to the movement. He began by acknowledging the extent of the protests, thus pushing the narrative of his boss, Alvaro Uribe, about the illegitimacy of the strike into the background. After this, he called for social conversation or “National Dialogue,” which is supposed to involve a series of meetings on the government’s development plans. These meetings are to be held between now and March 2020 and are to lead to some new legislative proposals. The content and methods of this “dialogue” are a minor adaptation of the dialogues the president holds in various regions each week. These are called “Talleres, construyendo país” and Duque has already conducted over 140 of them in his first year of office. They are a type of direct link with certain groups in order to project an image of closeness to the people, but they have done little to boost the credibility of the current administration.

The “National Dialogue” that has now been put on the table is seen to be a diversionary tactic to demobilize the protests as a weak propaganda tool of the government. The government is acting as if the dissatisfaction, along with the international conspiracy and irrational opposition, is due to a lack of information about the positive side of its policies. The government is merely generating mechanisms for propaganda and refusing to address the issues surrounding the protests. This is why the strike committee pulled out of the first meeting, with which the president planned to open talks with companies, mayors, and committees, etc. The aim was to only open dialogue with the sectors connected to him and ultimately push the mobilized sectors into the background. He is still refusing to talk about the implementation of the peace agreement, the withdrawal of the IMF’s proposed measures, the guarantee of life for leaders, and the vulnerability of young people, pensioners, and workers.

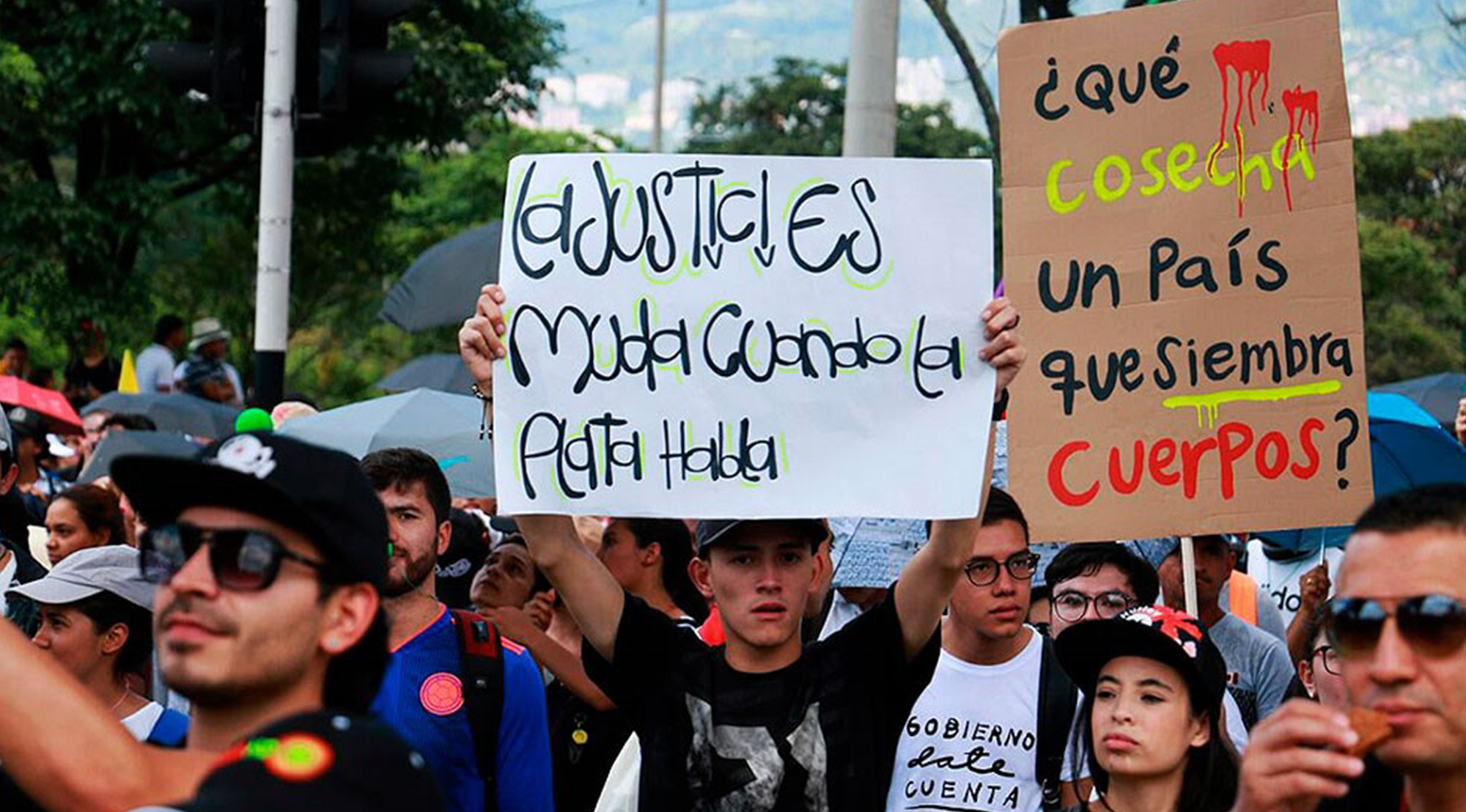

This indifference and ignorance towards instances of repressive violence that led to the death of young Dilan is infuriating for the people continuing the protest. With its attitude that public order policies and security can’t be part of the “dialogue” and even less a part of negotiations, the government has closed many doors. The people on the street are calling for the ESMAD to be taken out of the equation and for protest-related regulations to be modified. During the demonstrations that have been ongoing since November 21, placards demanding an immediate end to the bombardment and warfare commands as a response to the situation in rural areas have repeatedly stood out from the crowd. The topic of security policy is crucial for defending life, even more so in light of the current warfare strategies used by state security forces and the resurgence of practices that have not been used since the peak of paramilitarism.

ask: Thank you very much for your informative comments. Is there anything else you’d like to mention?

C.G.: In an interview with Vicky Dávila, senator Alvaro Uribe recommends that the government steps up its use of militarization to combat mobilization. He pointed out the strength of military presence when it comes to controlling cities. And curfew is another example. Uribe complained that this was not used as a permanent way of controlling the public. He recommends that police be used to oppose peaceful protest and the military with weapons of war to be mobilized against unauthorized demonstrations on public streets. Uribe also believes that the ESMAD should be strengthened instead of weakened and take a tougher approach to the disruption to public order. The basic message is: Zero concession to the demands of the strike; instead, unwaveringly repeating the proposals to reduce taxes for companies, make some amendments to health insurance for pensioners, and implement its labor reform. The strategy of these so-called elements in the tax reform is part of the “great dialogue” formula to keep things the same.